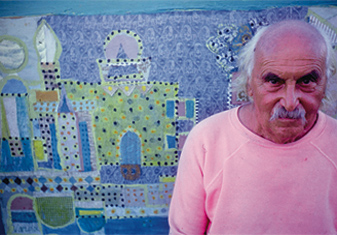

Jean “Yanko” Varda (1893-1971) was best known for his collages, which he made from bits of paper, textiles and paint, mounted on plywood.

Born to Greek parents in Smyrna (now Izmir,in Turkey), Varda, moved first to Paris as a young man, then to London, before traveling to New York for an exhibit of his work in 1939. He spent the war years in Big Sur and Monterey on the California Coast. After the war he moved to San Francisco, then across the Golden Gate Bridge to Sausalito, where he renovated an old ferryboat, called the Vallejo. The Vallejo was his home and his studio for the last two decades of his life.

As a young man Varda came under the influence of most of the important art movements of the early twentieth century, including Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism. He was an admirer of the bright palates used by Matisse and Bonnard and acknowledged a debt to the writings of the great artist Paul Klee. Raised in the Greek Orthodox religion, Varda also drew inspiration from the light and color of Byzantine icons and from the writings of Byzantine mystics.

Ultimately, however, Varda’s semi-abstract style, which he once described as “Passionate Lyricism,” was uniquely his own. For Varda the role of the artist was to bring joy and to transform ugliness into beauty. Nothing went to waste. Bits of paper and cloth were transformed into collages depicting beautiful women and exotic cityscapes or seascapes. Materials discarded in the making of one collage often served as inspiration for Varda’s next collage.

Varda applied his artistic philosophy to every aspect of his life. The Vallejo, renovated almost entirely from scavenged materials, was described by Varda’s friend Maya Angelou as “a happy child’s dream castle.” Using inexpensive fabric dyes, Varda transformed old clothes into brightly colored costumes. His gaily painted sailboats had lived earlier lives as metal lifeboats. A bit of dried cod, seasoned with fennel that grew wild on the shore next to the Vallejo, was transformed into a memorable meal. So too, as an artist, Varda treated the facts of his life as raw materials, and modified or transformed them at will to create parables and fables that, for Varda, represented, better than the unadorned facts, Varda’s personal version of the truth.

This site has been created by Varda's family in the hope of making sense of Varda’s art, and sorting out the myths from the facts about his life. We aim to weave a more complete picture of a man who embodied the artistic impulse and touched so many of those who knew him. We also hope to introduce Varda to a new generation who can be inspired and learn from his rich artistic and philosophical legacy.

Born to Greek parents in Smyrna (now Izmir,in Turkey), Varda, moved first to Paris as a young man, then to London, before traveling to New York for an exhibit of his work in 1939. He spent the war years in Big Sur and Monterey on the California Coast. After the war he moved to San Francisco, then across the Golden Gate Bridge to Sausalito, where he renovated an old ferryboat, called the Vallejo. The Vallejo was his home and his studio for the last two decades of his life.

As a young man Varda came under the influence of most of the important art movements of the early twentieth century, including Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism. He was an admirer of the bright palates used by Matisse and Bonnard and acknowledged a debt to the writings of the great artist Paul Klee. Raised in the Greek Orthodox religion, Varda also drew inspiration from the light and color of Byzantine icons and from the writings of Byzantine mystics.

Ultimately, however, Varda’s semi-abstract style, which he once described as “Passionate Lyricism,” was uniquely his own. For Varda the role of the artist was to bring joy and to transform ugliness into beauty. Nothing went to waste. Bits of paper and cloth were transformed into collages depicting beautiful women and exotic cityscapes or seascapes. Materials discarded in the making of one collage often served as inspiration for Varda’s next collage.

Varda applied his artistic philosophy to every aspect of his life. The Vallejo, renovated almost entirely from scavenged materials, was described by Varda’s friend Maya Angelou as “a happy child’s dream castle.” Using inexpensive fabric dyes, Varda transformed old clothes into brightly colored costumes. His gaily painted sailboats had lived earlier lives as metal lifeboats. A bit of dried cod, seasoned with fennel that grew wild on the shore next to the Vallejo, was transformed into a memorable meal. So too, as an artist, Varda treated the facts of his life as raw materials, and modified or transformed them at will to create parables and fables that, for Varda, represented, better than the unadorned facts, Varda’s personal version of the truth.

This site has been created by Varda's family in the hope of making sense of Varda’s art, and sorting out the myths from the facts about his life. We aim to weave a more complete picture of a man who embodied the artistic impulse and touched so many of those who knew him. We also hope to introduce Varda to a new generation who can be inspired and learn from his rich artistic and philosophical legacy.